Mentoring

Mentoring programs match a young person (mentee) with a more experienced person who is working in a non-professional capacity (mentor) to help provide support and guidance to the mentee in one or more areas of the mentee’s development. There are 4 types of Mentoring programs: Community, Juvenile Justice, School, and Youth Initiated.

Community-based Mentors are matched based on interests, hobbies, and compatibility so that the mentee and mentor can spend time together in the community and share activities they both enjoy. The goal of this type of mentoring relationship is to reduce substance abuse and antisocial behavior by establishing a support who can provide the youth with guidance.

Juvenile Justice-based Mentors are mentors who help youth with some involvement in the juvenile justice system (diversion through YRTC) so the mentor can demonstrate prosocial attitudes and behaviors while helping the youth navigate the juvenile justice system. The goal of this type of mentoring is the prevent the youth from having further involvement in the justice system.

School-based Mentors meet with youth on school premises to focus on school-related issues. The goal of this relationship is to improve youth attendance, grades, and attitudes toward school so that the youth is more likely to graduate.

Youth-Initiated Mentors are mentors that are identified by the youth as someone who is already a support or mentor for the youth. The program then helps to make sure the match is safe and supportive for the youth and to help develop natural mentors for more sustainable matches. The goal of this mentoring relationship is to help youth identify and sustain a healthy support system.

Evaluating Mentoring Programs

As part of our yearly evaluations for Community-based Juvenile Services Aid funded programs in fiscal year 2024, the JJI developed evaluation matrices to categorize important processes and outcomes for each program type evaluated. The following categories describe the important program processes and outcome indicators for mentoring programs. These categories can be used to assess the standing of a program in terms of whether it is successfully applying best practices and meeting expectations or common goals for a mental health program. For additional resources or to access articles referenced below, contact the JJI at unojji@unomaha.edu.

Meeting Data Standards

Any program assessment must start by reviewing what data is available on processes and outcomes. Incomplete data or small sample sizes (i.e. few client cases) increase the risk of error in analysis. Shreffler and Huecker (2023) describe what Type I and II errors are – with high risks for error we might fail to identify a positive impact that’s occurring or falsely state the program was effective when it wasn’t. Small sample sizes run the risk of an outlier (one or two cases with unique, or very low/high values in an outcome) skewing the results.

References: Shreffler, J. & Huecker, M.R. (2023, March 13). Type I and type II errors and statistical power. National Library of Medicine. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557530/.

Processes: Serving a Representative Population

Any community-based service and/or program should strive to serve eligible youth equitably across demographic groups. For mentoring programs, the best comparison group to compare the program’s referrals and enrollment rates to might be the county’s population. Or, if the program is school-based or juvenile justice-based, school enrollment or juvenile law enforcement contacts may serve as a better comparison.

The first step to creating a successful program is identifying an appropriate youth population to serve (Fernandes-Alcantara, 2015). Mentoring programs should be catered to all mentees, especially high-risk mentees. As the program progresses, it is essential to collect data on youth outcomes and create sustainability strategies. Proper training of mentors is essential to avoid premature closing of the relationship, especially for youth with multiple vulnerabilities. When matching mentees and mentors, it is important to limit the staff-to-match ratio for high-risk matches, to ensure more regular and intense contact (Kupersmidt et al., 2017).

References: Fernandes-Alcantara, A. L. (2015). Vulnerable youth: Federal mentoring programs and issues.

Kupersmidt, J. B., Stump, K. N., Stelter, R. L., & Rhodes, J. E. (2017). Mentoring program practices as predictors of match longevity. Journal of Community Psychology, 45(5), 630-645.

Processes: Matching Mentors to Mentees

The pairing of a mentor and mentee plays an essential role in the success of a relationship, as a mismatch could cause discomfort for the mentor and have negative outcomes for the mentee. Forcing relationships can lead to anger, resentment, and suspicion (Cox, 2005). When youth are not successfully matched, they lose enthusiasm for future program participation, eventually choosing not to participate at all (Spencer, 2007). Youth may be more likely to terminate a match when they do not feel that they have shared interests with their mentor or feel a disconnect in their communication. To increase chances of success, programs need to address the potential issues of lack of youth focus, unrealistic expectations of the youth, and low awareness of personal biases and how cultural differences shape relationships.

The Systems Theory of Mentoring highlights how important it is to create a collaborative relationship that goes beyond the mentor and mentee (e.g. parents, case management) (Lakind et al., 2015). Before the youth and mentor can begin working towards goal attainment, they must focus their time on building a strong relationship foundation based on trust. Relationships should be primarily youth focused, but it is also important for mentors to understand the environmental factors that play a role in youth beliefs and behaviors. Relationships must take a collaborative approach, so the youth play an active role in their successes, rather than being completely mentor guided.

References: Cox, E. (2005). For better, for worse: The matching process in formal mentoring schemes. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 13(3), 403–414. https://doi.org/10.1080/13611260500177484.

Lakind, D., Atkins, M., & Eddy, J. M. (2015). Youth mentoring relationships in context: Mentor perceptions of youth, environment, and the mentor role. Children and Youth Services Review, 53, 52-60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.03.007.

Spencer, R. (2007). “It’s Not What I Expected”: A Qualitative Study of Youth Mentoring Relationship Failures. Journal of Adolescent Research, 22(4), 331-354. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558407301915.

Processes: Match Quality

The quality of a mentor-mentee match can substantially impact how successful the mentorship is. Successful mentoring programs focus on interventions where the youth and the mentor spend more time together during each meeting, with the meetings occurring at least once a week, if not more regularly. It can be difficult for at-risk youth with challenging backgrounds to trust, and willingly enter a relationship with an adult/mentoring figure. This can delay the quality of the relationship, so research suggests that lengthy matches (12 months or longer) have the most significant effects on self-esteem, perceived social acceptance, perceived scholastic competence, and quality of parental relationships. Alternately, mentoring relationships that last less than three months can negatively impact each of these areas and matches that last for less than six months have not been found to have any significant effects in either direction. On a scale from low-key, moderate, or active mentoring relationships (in terms of activity and structure), youth have reported greatest success with matches characterized by moderate activity. Community based mentoring programs have the potential to decrease youth aggression when they promote resources such as collaboration between neighbors, available organizations and services, and accessible youth services (e.g., recreational and after school programs).

Youth mentoring programs that prioritize youth development focus on social-emotional, cognitive, and identity development by promoting relationships with nonparental adults. Mentoring programs show evidence of improving academic achievement and test scores. The effects of mentoring relationships are significantly greater when relationships persist for extended periods of time. A meta-analysis of 83 mentoring programs found that youth (both at-risk and non-at-risk) who participate in mentoring relationships benefit in multiple broad areas of development (DuBois et al., 2011). Programs that target youth who exhibit behavior difficulties have found greater success. The authors suggest that it is important to select mentors whose backgrounds and personal goals align with program goals and focus more on shared interests between the mentor and mentee, and less on demographic characteristics. The positive effect of mentoring relationships is elevated when mentors take on advocacy roles and make an effort to ensure the overall welfare of the youth.

References: DuBois, D. L., Portillo, N., Rhodes, J. E., Silverthorn, N., & Valentine, J. C. (2011). How effective are mentoring programs for youth? A systematic assessment of the evidence. Psychological science in the public interest, 12(2), 57-91.

Macomber, D., & Grigorenko, E. L. (2012). Mentor programming for at-risk youth. In Handbook of juvenile forensic psychology and psychiatry (pp. 439-452). Boston, MA: Springer US.

Processes: Discharging Youths Successfully

No matter how well a program implements best practices and effective interventions in their processes, if the program is not consistently engaging youth and maintaining the clients through the entire program to a successful discharge, they are unlikely to experience substantial change or progress. For mentoring, success might look like a mentor-mentee relationship continuing on past the evaluation period or even the end of the program. For mentoring programs to be successful, they need to avoid premature closing of match relationships and ensure that mentors complete the basic expectations for maintaining contact with their match (DuBois, 2021). Additionally, successful mentoring programs tend to focus on life and social skills, general youth development, academic enrichment, career exploration, leadership development, and college access (OJJDP, 2019). It is important to provide appropriate training and educational materials to provide mentors with the necessary tools to successfully maintain a match for an extended period.

References: Development Services Group, Inc. (2019). Youth mentoring and delinquency prevention literature review. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP). https://ojjdp.ojp.gov/model-programs-guide/literature-reviews/youth_mentoring_and_delinquency_prevention.pdf.

DuBois, D. L. (2021). Mentoring programs for youth: A promising intervention for delinquency prevention. National Institute for Justice Journal.

Outcomes: School-based mentoring outcomes

For school-based mentoring programs, a key goal is to improve student’s performance and attachment to school. Three school-based outcomes we evaluate are the student’s school attachment (e.g., engagement in class, relationships with teachers and school staff, appreciation for the value of education), grades, and attendance. The most positive effects of mentoring programs are seen when they target outcomes across academics, attitudes and motivation, social and interpersonal skills, and psychological and emotional status (Fernandes-Alcantara, 2015). When mentoring programs target the youth who stand most to benefit from them, they have the potential to positively affect youths’ grade point averages, high school graduation rates, and college acceptance rates as well (DuBois, 2021).

References: DuBois, D. L. (2021). Mentoring programs for youth: A promising intervention for delinquency prevention. National Institute for Justice Journal.

Fernandes-Alcantara, A. L. (2015). Vulnerable youth: Federal mentoring programs and issues.

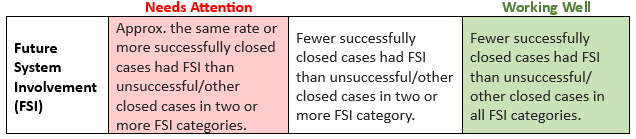

Outcomes: Reducing Future System Involvement

A major goal of the Community-based Juvenile Services Aid funding is to provide community-based services for juveniles who come in contact with the juvenile justice system and prevent youth from moving deeper into the system. All Community-based Aid (CBA) funded programs are evaluated on how effective they are at preventing future system involvement after youth are discharged from the program.

Mentoring programs can be effective at preventing or reducing system involvement. The Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP) has defined mentoring programs as a “consistent, prosocial relationship between an adult or older peer and one or more youth”. The goal of mentoring at-risk youth is to reduce risk factors for delinquency and enhance protective factors. A meta-analysis for several mentoring programs in the US has found mentoring programs can significantly reduce delinquency and substance abuse, and improve youth’s school grades and attendance, and psychological functioning. Another study by DuBois and colleagues (2002) found that youth who had been previously arrested, prior to participating in a mentoring program, had lower arrest rates in comparison to youth not in a program. To be most effective, mentoring programs need to be tailored to match the needs of the youth that they are serving (e.g., understanding cultural awareness for ethnic minority youth, economic and cultural gaps that refugee youth face, how to navigate the health system and life with youth who have diagnosed mental illnesses).

References: Development Services Group, Inc. (2019). Youth mentoring and delinquency prevention literature review. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP). https://ojjdp.ojp.gov/model-programs-guide/literature-reviews/youth_mentoring_and_delinquency_prevention.pdf.

DuBois, D. L., Holloway, B. E., Valentine, J. C., & Cooper, H. (2002). Effectiveness of mentoring programs for youth: A meta‐analytic review. American journal of community psychology, 30(2), 157-197.https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014628810714

Additional Resources

JCMS Guides

Community Mentoring JCMS User Guide

Justice-based Mentoring JCMS User Guide

School-based Mentoring JCMS User Guide

Youth-initiated Mentoring JCMS User Guide

*You can find more JCMS training materials and videos on the Trainings & Tools page.

Resources for mentoring

OJJDP’s National Mentoring Resource Center provides a collection of mentoring handbooks, curricula, manuals, and other resources that practitioners can use to implement and further develop program practices.

The Center for Evidence-Based Mentoring is a collaboration between MENTOR and the University of Massachusetts-Boston led by leading mentoring researcher Dr. Jean Rhodes. The Center’s mission is to drive evidence-based innovation that advances mentoring practice and helps to bridge gaps in mental health care among young people, particularly in marginalized communities. Subscribe to the Chronicle to receive regular updates on current evidence-based practices in mentoring!

Dr. David DuBois with the University of Illinois at Chicago hosts a Youth Mentoring Listserve designed to serve as a virtual community for sharing of ideas and resources among researchers and practitioners in the area of youth mentoring. To join, e-mail Dr. DuBois at dldubois@uic.edu.

Research &

Best Practices

for Mentoring

Youth Mentoring and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP Literature Review, 2019)

The focus of this literature review is on the different types of mentoring models for youth at risk or already involved in the juvenile justice system and their various components, including setting, mode of delivery, and target population. The review also provides a summary of mentoring programs that have been evaluated and discusses gaps in research on program implementation. There is also additional information about research and effectiveness available on the OJJDP National Mentoring Resource Center. PDF

Elements of Effective Practice for Mentoring, 4th Edition (The National Mentoring Partnership, 2015)

Mentoring continues to grow in diverse directions and is embedded into myriad program contexts and services. The fourth edition of the Elements of Effective Practice for Mentoring™ is intended to give this generation of practitioners a set of programmatic standards that will empower every agency and organization, and raise the bar on what quality mentoring services look like. We hope this edition benefits programs of all sizes and funders from every sector in creating, sustaining, and improving mentoring relationships because they are critical assets in young people’s ability to thrive and strive. PDF

Mentoring programs for youth: A promising intervention for delinquency prevention (DuBois, 2021)

Youth mentoring programs have been shown to be a successful strategy for reducing negative behaviors and promoting resilience among high-risk youth. Youth mentoring can have several formats, including one-to-one mentoring, group, school, or community mentoring. For mentoring programs to be successful, they need to avoid premature closing of match relationships and ensure that mentors complete the basic expectations for maintaining contact with their match. Providing appropriate training and educational materials helps provide mentors with the necessary tools to successfully maintain a match for an extended period. When mentoring programs target the youth who stand most to benefit from them, they have the potential to positively affect youths’ grade point averages, high school graduation rates, and college acceptance rates. PDF

Foundations of Successful Youth Mentoring (The Hamilton Fish Institute on School and Community Violence & The National Mentoring Center at Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory, 2007)

The Effective Strategies for Providing Quality Youth Mentoring in Schools and Communities series, sponsored by the Hamilton Fish Institute on School and Community Violence, is designed to give practitioners a set of tools and ideas that they can use to build quality mentoring programs. Each title in the series is based on research (primarily from the esteemed Public/Private Ventures) and observed best practices from the field of mentoring, resulting in a collection of proven strategies, techniques, and program structures. Revised and updated by the National Mentoring Center at the Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory, each book in this series provides insight into a critical area of mentor program development: Foundations of Successful Youth Mentoring—This title offers a comprehensive overview of the characteristics of successful youth mentoring programs. Originally designed for a community-based model, its advice and planning tools can be adapted for use in other settings. [PDF][5] [5]: /s/Foundations-of-Successful-mentoring-2007-HamiltonFishInstitute.pdf

How Effective Are Mentoring Programs for Youth? A Systematic Assessment of the Evidence (DuBois, et al 2011)

During the past decade, mentoring has proliferated as an intervention strategy for addressing the needs that young people have for adult support and guidance throughout their development. Currently, more than 5,000 mentoring programs serve an estimated three million youths in the United States. Funding and growth imperatives continue to fuel the expansion of programs as well as the diversification of mentoring approaches and applications. Important questions remain, however, about the effectiveness of these types of interventions and the conditions required to optimize benefits for young people who participate in them. In this article, we use metaanalysis to take stock of the current evidence on the effectiveness of mentoring programs for youth. As a guiding conceptual framework for our analysis, we draw on a developmental model of youth mentoring relationships (Rhodes, 2002, 2005). This model posits an interconnected set of processes (socialemotional, cognitive, identity) through which caring and meaningful relationships with nonparental adults (or older peers) can promote positive developmental trajectories. These processes are presumed to be conditioned by a range of individual, dyadic, programmatic, and contextual variables. Based on this model and related prior research, we anticipated that we would find evidence for the effectiveness of mentoring as an approach for fostering healthy development among youth. We also expected that effectiveness would vary as a function of differences in both program practices and the characteristics of participating young people and their mentors.PDF

Testing the Impact of Mentor Training and Peer Support on the Quality of Mentor-Mentee Relationships and Outcomes for At-Risk Youth (Peaslee & Teye, 2015)

National trends point to the increased popularity of mentor programs to enhance protective factors and decrease poor life outcomes for at-risk youth. Generally, substantial empirical evidence confirms improved outcomes for at-risk youth involved in mentoring programs; however, there is limited empirical evidence linking mentor training and programmatic support to the strength of mentoring relationships and youth outcomes. This evaluation investigates the impact of Enhanced Mentor Training and Peer Support for mentors on the quality of mentor/mentee relationships and mentee outcomes. Research was conducted in conjunction with an affiliate of Big Brothers Big Sisters of America in Harrisonburg, Virginia, an established mentoring program that has consistently surpassed national standards in all areas of quality metrics. A total of 459 matches were enrolled in the three-year study. We utilized a between subject experimental design, with three randomly assigned intervention groups: a) Enhanced Mentor Training b) Peer Support, and c) an Interaction Intervention. The report concludes with recommendations from an implementation analysis and an outcome evaluation to inform the work of mentoring researchers and practitioners. PDF

Mentoring Together: A Literature Review of Group Mentoring (Huizing, 2012)

Researchers have shown the benefits of mentoring in both personal and professional growth. It would seem that group mentoring would only enhance those benefits. This work represents a literature review of peer-reviewed articles and dissertations that contribute to the theory and research of group mentoring. This work reviews the articles that contributed to the development of group mentoring theory as well as relevant research. Four primary types of group mentoring emerge—peer group, one-to-many, many-to-one, and many-to-many. Despite over 20 years of research, significant gaps remain in the research methods, demographic focus, and fields of study. The review concludes with recommendations for future research. PDF

Twelve-Year Professional Youth Mentoring Program for High Risk Youth: Continuation of a Longitudinal Randomized Controlled Trial (Eddy, et al 2015)

This study investigated impacts of a professional mentoring program, Friends of the Children (FOTC), during the first 5 years of a 12 year program. Participants (N = 278) were early elementary school aged boys and girls who were identified as “high risk” for adjustment problems during adolescence and emerging adulthood, including antisocial behavior and delinquency, through an intensive collaborative school-based process. Participants were randomly assigned to FOTC or a referral only control condition. Mentors were hired to work full time with small caseloads of children and were provided initial and ongoing training, supervision, and support. The program was delivered through established non-profit organizations operating in four major U.S. urban areas within neighborhoods dealing with various levels of challenges, including relatively high rates of unemployment and crime. Recruitment into the study took place across a three year period, and follow-up assessments have been conducted every six months. Data have been collected not only from children, but also from their primary caregivers, their mentors, their teachers, and their schools (i.e., official school records). Strong levels of participation in study assessments have been maintained over the past 8 years. Most children assigned to the FOTC Intervention condition received a mentor, and at the end of the study, over 70% still had mentors. While few differences were found between the FOTC and control conditions for the first several years of the study, two key differences, in child "externalizing" behaviors and child strengths, emerged at the most recent assessment point, which on average was after 5 years of consistent mentoring. To date, outcomes do not appear related to the amount of mentor-child contact time or the quality of the mentor-child relationship. Analyses are ongoing, and additional funding is being sought to continue the study forward. PDF

Mentee Risk Status and Mentor Training as Predictors of Youth Outcomes (Kupersmidt, et al 2017)

Archival national data from a wide range of mentoring programs were examined to determine whether mentee risk status predicted match outcomes. In addition, archival national data from Big Brothers Big Sisters agencies accompanied by program practice self-assessments from a subset of agencies were examined to determine the relationship between program practices and outcomes for mentoring relationships, in general, as well as for mentoring relationships of special populations of youth (i.e., children with an incarcerated parent, youth in foster care). Mentees who were adolescents when first matched or with exposure to many risk factors such as exhibiting antisocial behavior problems or experiencing many stressful life experiences were less likely to have mentoring relationships that are effective and long lasting; however, mentoring program practices make a difference in match longevity, even with high-risk youth. Specifically, the sum total number of both benchmark program practices and standards described in the Elements of Effective Practice for Mentoring (EEPM; Third Edition) implemented by mentoring programs were associated with match length and long-term relationships; however, neither predicted premature match closure. These findings were true for matches in general, as well as for matches including youth in foster care. Notably, the Training Standard in the EEPM predicted match length of mentoring relationships, in general. In addition, children of incarcerated parents (COIP) have shorter mentoring relationships, and have lower grades, school attendance, and parental trust after one year of mentoring, compared to youth who are non-COIP. In addition, providing specialized mentor training on issues associated with mentoring of children of incarcerated parents was associated with longer and stronger matches and mentees having higher educational expectations. Mentees who were children of incarcerated parents (COIP) experienced benefits from mentoring programs that received additional funding specifically for serving COIP. Given the importance of having a set of standards of practice for the field of youth mentoring that define both research-and safety-based program practices, a model for the development of practice guidelines and recommendations for the youth mentoring field was adapted from the health care literature on the development of Clinical Practice Guidelines. This model includes replicable and transparent procedures that can be used to update the EEPM as well as create supplemental guidelines for special populations of mentees or mentors, or special mentoring intervention models or settings. PDF

Training New Mentors (The Hamilton Fish Institute on School and Community Violence & The National Mentoring Center at Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory, 2008)

The “Effective Strategies for Providing Quality Youth Mentoring in Schools and Communities” series, sponsored by the Hamilton Fish Institute on School and Community Violence, is designed to give practitioners a set of tools and ideas that they can use to build quality mentoring programs. Each title in the series is based on research (primarily from the esteemed Public/Private Ventures) and observed best practices from the field of mentoring, resulting in a collection of proven strategies, techniques, and program structures. Revised and updated by the National Mentoring Center at the Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory, each book in this series provides insight into a critical area of mentor program development: Training New Mentors—All mentors need thorough training if they are to possess the skills, attitudes, and activity ideas needed to effectively mentor a young person. This guide provides ready-to-use training modules for your program. PDF