Mediation and Restorative Justice

Restorative Justice is based on the core belief that “all human beings are worthy and interconnected” (Evans & Vaandering, 2022, p. 10). Restorative practices focus on bringing together individuals who have caused harm and those harmed, as well as members of the parties’ community to find ways to heal harms caused, strengthen relationships, and retain or restore the individual who caused harm in their community. Restorative practices can serve as both prevention and intervention.

Mediation is a restorative practice used in schools and the juvenile justice system and is a form of conflict resolution in which trained leaders help the victim(s) and offender work together to resolve disputes. Mediators do not make judgements or offer advice, and they have no power to force decisions. Victims are able to have input into an offender’s sentence. Includes victim impact statements, defining the restitution owed, or other forms of affecting resolution of a juvenile justice case. Other stakeholders may participate in the process as well.

Evaluating Mediation Programs

As part of our yearly evaluations for Community-based Juvenile Services Aid funded programs in fiscal year 2024, the JJI developed evaluation matrices to categorize important processes and outcomes for each program type evaluated. The following categories describe the important program processes and outcome indicators for mediation/restorative justice programs. These categories can be used to assess the standing of a program in terms of whether it is successfully applying best practices and meeting expectations or common goals for a mediation program. For additional resources or to access articles referenced below, contact the JJI at unojji@unomaha.edu.

Meeting Data Standards

Any program assessment must start by reviewing what data is available on processes and outcomes. Incomplete data or small sample sizes (i.e. few client cases) increase the risk of error in analysis. Shreffler and Huecker (2023) describe what Type I and II errors are – with high risks for error we might fail to identify a positive impact that’s occurring or falsely state the program was effective when it wasn’t. Small sample sizes run the risk of an outlier (one or two cases with unique, or very low/high values in an outcome) skewing the results.

References: Shreffler, J. & Huecker, M.R. (2023, March 13). Type I and type II errors and statistical power. National Library of Medicine. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557530/.

Processes: Serving a Representative Population

Any community-based service and/or program should strive to serve eligible youth equitably across demographic groups. For mediation programs, the best comparison group to compare the program’s referrals and enrollment rates to will vary depending on the program’s population or referral source. If the program is based in a school, the best comparison population might be the school’s enrollment (which can be obtained from the Nebraska Department of Education website), or disciplined students if only serving as an intervention program. If, instead, the program receives referrals solely from diversion programs, a better comparison population would be the local county’s diversion population.

Restorative practices can be an effective tool for addressing disparities in the juvenile justice system and the school system. In their review of research on school-based restorative justice programs, Kline (2016) highlighted how restorative practices - those meant to be inclusionary and nonpunitive - could be successful in reducing disparities in school discipline rates for minority students. Addressing school discipline disparities can play a pivotal role in reducing disproportionate justice system contact for at-risk youth (Kline, 2016).

There is a long history of school discipline serving as a pathway into greater system involvement - a phenomenon termed the ‘school-to-prison pipeline.’ Zero Tolerance policies meant to target dangerous behaviors like gun violence in schools have resulted in widespread use of ‘exclusionary discipline’ (like suspensions and expulsions') across the country. Like with the justice system, these punitive disciplinary responses are consistently used much more often with Black students and students with disabilities (Simson, 2012).

References: Kline, D. M. S. (2016). Can restorative practices help to reduce disparities in school discipline data? A review of the literature. Multicultural Perspectives, 18(2), 97-102.

Simson, D. (2012). Restorative justice and its effects on (racially disparate) punitive school discipline. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2107240

Processes: Making Reparations

For mediation programs, creating a reparation agreement between the individual who caused harm and those they harmed can be a key step in the restorative process. Reparation agreements are a form of ‘corrective justice’ that serve to address the needs of those harmed and require responsibility taking by those who have caused harm. Walker (2006) explains there is not one way to go about making reparation agreements and that these agreements can address the needs of all those involved - not just the individual(s) directly harmed. Mediation conferences and reparation agreements can also help a community (for example a school community including teachers and support staff) identify and address the needs of the youth who caused harm, in order to prevent future incidents.

The goal of reparation agreements should not be vengeance or retribution, but instead of repair and redress. To this end, reparation agreements cannot be forced upon harm-doers, but must be agreed upon and set in motion through their own desire to repair the harms they’ve caused (Sharpe, 2013). In describing the types and methods of reparation, Sharpe (2013) explains reparation can be either materialistic or symbolic - sometimes involving an apology, restitution, or physical repair of damaged property (for example, replanting a community garden that was vandalized). Reparation in any form can serve to directly repair damage caused, can provide victims space to be heard and vindicated, can locate responsibility, and can help victims “regain equilibrium” (Sharpe, 2013, p. 29).

References: Walker, M. U. (2006). Restorative justice and reparations. Journal of Social Philosophy, 37(3), 377-395. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9833.2006.00343.x

Sharpe, S. (2013). The idea of reparation. In G. Johnstone & D. Van Ness (Eds.), Handbook of restorative justice (pp. 24-40). Routledge.

OUTCOMES: COMPLETED Reparation Agreements

Beyond creating reparation agreements, an effective mediation program should result in high rates of successfully completed agreements. In Johnstone and Van Ness’s (2013) Handbook for Restorative Justice, successfully completing reparation agreements and improving victim satisfaction are proposed as additional positive outcomes for evaluating restorative justice programs. Indeed, Bazemore and Elis argue “The primary goal for any restorative intervention is to repair, to the greatest extent possible, the harm caused to victims, offenders and communities who have been injured by crime. This goal is achieved by focusing attention on the dialogue process in a restorative encounter and on the extent to which the offender (often with the help of others) takes action to make things right” (p. 404).

Sharpe (2013) recommends three ‘optimal’ conditions for creating reparation agreements to increase the likelihood they are successfully completed and have a positive impact on all involved.

First, reparation agreements should be tailored to the specific harms done. Tailoring the reparation agreements also increases the likelihood individuals take responsibility for their actions and better understand how they caused harm. Reparation agreements should also be determined by the stakeholders, “primarily the victim, who will live with the outcome, and the offender, who is responsible for the repair, as well as others who might also be affected” (p. 30). Finally, reparations are most successful when offered, and/or readily agreed to, by the individual who caused harm.

In general, restorative justice processes facilitate the optimal conditions for effective reparation, insofar as they involve all interested stakeholders, help victims articulate the full range of harms they have experienced and assist offenders in finding ways to make amends (Sharpe, 2013, p. 32).

Additionally, Bazemore and Elis (2013) recommend not discussing the agreement in the preparation or early stages of mediation so the process does not become too focused on “settlement-driven mediation” but instead focused on supporting victim and offender dialogue (p. 407).

References: Johnstone, G. & Van Ness, D. W. (Eds.). (2013). Handbook of restorative justice. Routledge.

Sharpe, S. (2013). The idea of reparation. In G. Johnstone & D. Van Ness (Eds.), Handbook of restorative justice (pp. 24-40). Routledge.

Bazemore, G. & Elis, L. (2013). Evaluation of restorative justice. In G. Johnstone & D. W. Van Ness (Eds.), Handbook of restorative justice (pp. 397-425). Routledge.

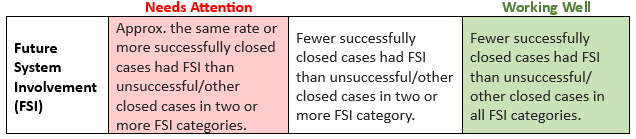

Outcomes: Reducing Future System Involvement

A major goal of the Community-based Juvenile Services Aid funding is to provide community-based services for juveniles who come in contact with the juvenile justice system and prevent youth from moving deeper into the system. All Community-based Aid (CBA) funded programs are evaluated on how effective they are at preventing future system involvement after youth are discharged from the program.

Restorative justice and mediation can effectively reduce reoffending while also producing other beneficial outcomes, such as improve victim satisfaction, greater prosocial involvement from individuals who previously caused harm, and stronger relationships between community members (Kimbrell et al., 2023). Several systematic reviews and meta-analyses have found support for restorative justice programs’ effectiveness at reducing recidivism and further system involvement (see Bradshaw & Roseborough, 2005; Hayes & Daly, 2003; Kimbrell et al., 2023; Latimer et al., 2005; Strang et al., 2013, Wilson et al., 2017; Wong et al., 2016).

From these reviews, a number of key elements of restorative programs have been identified as associated with greater reductions in recidivism. Hayes and Daly (2003) found “youthful offenders who were observed to be remorseful and whose outcomes were reached by consensus were less likely to reoffend” (p. 725) - further emphasizing the importance of a collaborative approach to reparation agreement development. Restorative diversion programs have also been found to significantly reduce recidivism, particularly for low-risk and first-time offenders (Wilson et al., 2017; Wong et al., 2016).

References: Bradshaw, W., & Roseborough, D. (2005). Restorative justice dialogue: The impact of mediation and conferencing on juvenile recidivism. Federal Probation, 69, 15.

Hayes, H., & Daly, K. (2003). Youth justice conferencing and reoffending. Justice Quarterly, 20(4), 725-764. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418820300095681

Kimbrell, C. S., Wilson, D. B., & Olaghere, A. (2023). Restorative justice programs and practices in juvenile justice: An updated systematic review and meta‐analysis for effectiveness. Criminology & Public Policy, 22(1), 161–195. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12613

Latimer, J., Dowden, C., & Muise, D. (2005). The effectiveness of restorative justice practices: A meta-analysis. The Prison Journal, 85(2), 127–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032885505276969

Strang, H., Sherman, L. W., Mayo‐Wilson, E., Woods, D., & Ariel, B. (2013). Restorative justice conferencing (RJC) using face‐to‐face meetings of offenders and victims: Effects on offender recidivism and victim satisfaction. A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 9(1), 1–59. https://doi.org/10.4073/csr.2013.12

Wilson, D. B., Olaghere, A., & Kimbrell, C. S. (2017). Effectiveness of restorative justice principles in juvenile justice: A meta-analysis. U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

Wong, J. S., Bouchard, J., Gravel, J., Bouchard, M., & Morselli, C. (2016). Can at-risk youth be diverted from crime?: A meta-analysis of restorative diversion programs. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 43(10), 1310–1329. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854816640835

Additional Resources

JCMS Guides

*You can find more JCMS training materials and videos on the Trainings & Tools page.

Resources for Restorative Justice & Mediation Programs

There are numerous books, handbooks, and guides available explaining what restorative justice is, how to implement a restorative program, and how to meet the goals of a restorative program. The Handbook of Restorative Justice, edited by Gerry Johnstone and Daniel Van Ness (2013), is particularly useful and multiple chapters were cited above in the JJI’s evaluation guide for mediation programs.

Living Justice Press also publishes a series of “Little Books” covering a wide range of restorative justice topics, including Race and Restorative Justice (Davis, 2019), Youth Engagement in Restorative Justice (Aquino et al., 2021), and Restorative Justice in Education (Evans & Vaandering, 2022).

Local Resources

The Nebraska Office of Dispute Resolution (ODR) “promotes mediation and RJ in the courts and in our families and communities.” The ODR provides resources and guidance for implementing RJ, including parent education, guidance on mediating a parent plan, and assistance finding a mediator. The ODR also approves mediation centers and mediators across the state that can directly help with a variety of issues. There are currently six approved Mediation Centers across Nebraska.

The Nebraska Mediation Association’s (NMA) mission is to “promote creative and constructive engagement through professional development, collaborative partnerships, facilitation, mediation, restorative justice, and conflict engagement training to practitioners, professionals, and others throughout the State of Nebraska.” There are several ways to stay connected with NMA, including joining their mailing list, participating in their weekly book club, or attending one of their regular events/webinars.

The International Institute of Restorative Practice (IIRP) offers “flexible graduate-level programs geared toward working professionals that allow you to study where you live and work.” The IIRP’s mission is to “strengthen relationships, support communities, influence social change, and broaden the field of restorative practices by partnering with practitioners, students, and scholars.”

The IIRP also hosts the Restorative Works! Podcast, with episodes every Thursday covering a range of restorative topics and issues.

The National Center on Restorative Justice (NCORJ) also provides training, resources, and assistance “to train the next generation of justice leaders and to support and lead research focusing on restorative justice.” Their goal is to support RJ initiatives in “addressing social inequities to improve criminal justice policy and practice in the United States.”