Mental Health

Mental Health programs work with youth to promote the youth’s recognition of their abilities and help identify coping skills to assist with improving mental health well-being. A mental health program may use screening tools and assessments to identify mental health diagnoses to further tailor the program to meet the needs of the youth. Treatment focused mental health programs provide services to the youth that will help promote cognitive mental functioning through client-focused therapeutic options.

As part of our yearly evaluations for Community-based Juvenile Services Aid funded programs in fiscal year 2024, the JJI developed evaluation matrices to categorize important processes and outcomes for each program type evaluated. The following categories describe the important program processes and outcome indicators for mental health programs. These categories can be used to assess the standing of a program in terms of whether it is successfully applying best practices and meeting expectations or common goals for a mental health program. For additional resources or to access articles referenced below, contact the JJI at unojji@unomaha.edu.

Meeting Data Standards

Any program assessment must start by reviewing what data is available on processes and outcomes. Incomplete data or small sample sizes (i.e. few client cases) increase the risk of error in analysis. Shreffler and Huecker (2023) describe what Type I and II errors are – with high risks for error we might fail to identify a positive impact that’s occurring or falsely state the program was effective when it wasn’t. Small sample sizes run the risk of an outlier (one or two cases with unique, or very low/high values in an outcome) skewing the results.

References: Shreffler, J. & Huecker, M.R. (2023, March 13). Type I and type II errors and statistical power. National Library of Medicine. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557530/.

Processes: Serving a Representative Population

Any community-based service and/or program should strive to serve eligible youth equitably across demographic groups. For mental health programs, the best comparison group to compare the program’s referrals and enrollment rates to might be the county’s population. Or, if the program receives referrals only from a particular school or through the county’s diversion program, the school enrollment or diversion population may serve as a better comparison.

In the research, there is evidence that White and female juveniles are more likely to receive mental health services than youth of other races or male youth. Herz (2001) found that one third of cases in their sample of juvenile offenders were White and fewer than 12% were female. However, Herz also found that White juveniles were four times as likely to receive a mental health placement than Black youth (19% of White youth versus 5% of Black youth) and girls were four times as likely to receive a mental health placement than boys (33% versus 7%). Herz (2001) concluded that “race and gender were significantly related to mental health placements regardless of other important factors.” Garland and colleagues (2005) also found racial disparities in the use of mental health services. Specifically, African American and Asian American/Pacific Islander youth were half as likely to receive any mental health service in comparison to Non-Hispanic White youth.

References: Garland, A.F., Lau, A.S., Yeh, M., McCabe, K., Hough, R., & Landsverk, J.A. (2005). Racial and ethnic differences in utilization of mental health services among high-risk youths. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(7). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1336.

Herz, D. C. (2001). Understanding the Use of Mental Health Placements by the Juvenile Justice System. Journal of Emotional & Behavioral Disorders, 9(3), 172. https://doi-org /10.1177/106342660100900303.

Processes: Discharging Youths Successfully

No matter how well a program implements best practices and effective interventions in their processes, if the program is not consistently engaging youth and maintaining the clients through the entire program to a successful discharge, they are unlikely to experience substantial change or progress.

Menjivar (2023) with Mental Health America notes that often youth voices “are shut out of the design” (para. 1) of mental health programs. Mental health intervention and prevention models that are youth-centered and even designed with youth collaboration can be more successful at keeping youth engaged throughout the program.

References: Menjivar, J. (2023, May). 5 ideas for building youth-centered mental health programs. Mental Health America. https://mhanational.org/blog/5-ideas-building-youth-centered-mental-health-programs.

Outcomes: Youths’ Progress at Discharge

Tracking youths’ progress at discharge allows programs to measure positive or negative changes within patients and interventions which can help show effectiveness. Jaffa and Stott (1999) found, “of those who made significant gains during treatment... approximately one quarter improved further during follow-up period [and] approximately one half maintained improvement...”(p. 298). A way to improve youths’ experiences at discharge is to create a discharge plan. Creating a plan will not only help an individual to have a successful discharge, but can also help an individual stay successful after discharge. This can be particularly important in decreasing rehospitalization or returning to a program.

References: Jaffa, T, and C Stott. (1999) Do inpatients on adolescent units recover? A study of outcome and acceptability of treatment. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 8(4), 292–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s007870050104.

Xiao, S., Tourangeau, A., Widger, K., & Berta, W. (2019). Discharge planning in mental healthcare settings: A review and concept analysis. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 28(4), 816-832. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12599.

Outcomes: Reducing Future System Involvement

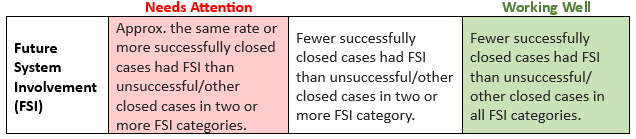

A major goal of the Community-based Juvenile Services Aid funding is to provide community-based services for juveniles who come in contact with the juvenile justice system and prevent youth from moving deeper into the system. All Community-based Aid (CBA) funded programs are evaluated on how effective they are at preventing future system involvement after youth are discharged from the program.

Mental health systems, such as community-based care can reduce/delay entry into the Juvenile Justice System and can reduce recidivism (i.e., reoffending) in youth they serve when used properly. Foster and colleagues (2004) showed that integrated care provides a greater decrease in juvenile justice entry and recidivism than coordinated care, but both types decreased the likelihood of entry and recidivism.

References: Foster, M.E., Qaseem, A., & Connor, T. (2004). Can better mental health services reduce the risk of juvenile justice system involvement? American Journal of Public Health, 94(5), 859-865. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.94.5.859.

LB561. Nebraska Revised Statute 43-2404.02 (2013).

Additional Resources

JCMS Guides

*You can find more JCMS training materials and videos on the Trainings & Tools page.